Projective Insights

Projective Geometry is the branch of geometry dealing with the properties and invariants of geometric figures under projection. In older literature, projective geometry is sometimes called “higher geometry,” “geometry of position,” or “descriptive geometry”. The most amazing result arising in projective geometry is the duality principle, which states that a duality exists between theorems such as Pascal’s theorem and Brianchon’s theorem which allows one to be instantly transformed into the other. More generally, all the propositions in projective geometry occur in dual pairs, which have the property that, starting from either proposition of a pair, the other can be immediately inferred by interchanging the parts played by the words “point” and “line.”

My interest in PGA is a natural outgrowth of my long-standing interest in projective geometry. One of the phases in this process was my work at the Geometry Center at the University of Minnesota (1987-1993), where we created interactive visualizations of hyperbolic and spherical space for the first time using the projective models of these spaces, under the guidance of the late Bill Thurston.

It was natural then that when I went back (quite a bit later) to get a Ph. D. I looked into how not just to make pictures but how to do physics in these non-euclidean spaces. That’s when I became aware of a certain family of geometric algebras that I have since christened PGA and that formed the technical foundation for my thesis (Technical University Berlin, 2011).

The non-euclidean cases were already familiar to the pioneers of GA in the 1870’s such as Clifford and Klein; the euclidean case, however, is a bit tricky and was first enunciated by Jon Selig in around 2000. I have gone on to explore PGA more thoroughly and have published a series of articles devoted especially to the euclidean case; since I think it’s a fantastic tool — both conceptually and practically — for doing euclidean geometry. It includes as sub-algebras the well-known vector, quaternion, and dual (or bi-) quaternion algebras, but offers much more besides. It deserves to be much better-known than it is, especially in the applied mathematics and engineering community. In the article “Geometric algebras for euclidean geometry” I have shown that for classical “flat” euclidean geometry, PGA exhibits distinct advantages over the alternative approaches. It serves also as an ideal stepping-stone both scientifically and pedagogically to more complex GAs such as CGA. This article and others can be accessed at my PGA resource page.

The development of mathematics in the 19th century was unique: radical advances were made in every field but an underlying unity was preserved so that leading mathematicians still had an overview of the whole. The transition to the 20th century saw an increasing specialization, the cost was a splintering of the whole. Decisions were made that in retrospect appear to have been motivated more by an ideology of abstraction than by a balanced practical judgment. PGA I think has the potential to stand as “living proof” that 19th-century mathematics still has much to offer to the contemporary community of applied geometry. It unifies two of William Clifford’s greatest inventions: biquaternions and geometric algebra, in the simplest, most elegant way imaginable, and provides an unsurpassed framework for doing kinematics and rigid body mechanics in euclidean (or non-euclidean) space.

On the other hand, it’s also important to note that PGA also contains seeds for the future. I’m particularly interested in this regard in dual euclidean space, which is a metric geometry obtained from euclidean geometry by dualizing it. It arises naturally as a variant of PGA. It was described by Felix Klein in the 19th century but was so unfamiliar that is was relegated to being a curiosity. There is an increasing volume of research, however, indicating that it might play an important role in future science by balancing a certain one-sidedness in our contemporary spatial awareness. Ch. 10 of my thesis contains an introduction to this fascinating theme, available on the resource site above.

The prospect of using PGA in this way to better understand Nature also resonates with the 19th-century heritage. The great pioneers of that era — Möbius, Plücker, Riemann, Grassmann, Clifford, and Klein, among others — were all inspired, in their mathematical research, by physical questions. I personally think that mathematics needs such real-world connections in order to develop healthily and am curious to see whether PGA can help to strengthen such connections.

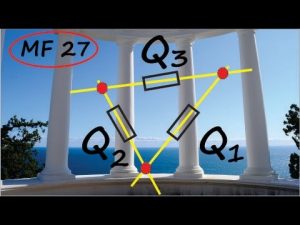

I am no expert on Wildberger’s Rational Trigonometry, although I find the basic idea intriguing. One avoids the messiness of evaluating irrational and/or transcendental functions by working with the sine/cosine of the angle rather than with the angle itself, the square of the norm of a vector instead of the norm, etc. A friend loaned me a copy of Wildberger’s book as I was finishing my thesis and I made it a project to see how many of his results I could rephrase in the language of PGA. I was surprised myself by how well this process went. For example, the fundamental concepts of rational trigonometry — quadrance and spread — reveal themselves in PGA to be precisely dual to each other, a fact not obvious in the original treatment. Furthermore, many of the derivations in PGA are, in my humble opinion, clearer and shorter than the coordinate-based ones in the original. I determined that the whole subject could probably be rephrased in this way using PGA but the lack of time has prevented further work in this direction. This experience is typical when I “translate” standard treatments of Euclidean geometry into PGA: often I discover a remarkable conciseness and elegance in the PGA version.

I am not a software purist; I used whatever helps me get the job done. Robustness and thorough documentation are my primary criteria. All my PGA investigations also involve visualization, so these two themes go hand-in-hand. Among commercial products, my favorite tool is Mathematica and I use it for prototype development. In fact, I used Mathematica to check all the results in my thesis for correctness.

For production software, I favor public domain software. Throughout my career (since writing my first hidden-surface removal algorithm on punch cards in 1978 at UNC-CH) I have developed such visualization software in parallel to my mathematical interests, as I found that existing 3D tools were/are generally not flexible enough to render what I wanted to. I worked on the geomview project at the Geometry Center in the early 90’s. The latest incarnation in this direction is the Java 3D scene graph jReality, which I’ve been involved with at the TU Berlin since 2003. Like geomview, it is built on the foundation of projective geometry and can be then specialized to support different metric geometries such as Euclidean, hyperbolic, and spherical geometry, and has been further specialized by me for my PGA research.

I have also been learning Haskell recently since its pure functional, polymorphic style is particularly well-suited to reliably mapping mathematical domains such as PGA and it seems to be gaining quite a large following. I have looked at other GA packages, hoping to apply them to PGA, but at the time I looked none of them supported a degenerate metric (a key feature of Euclidean PGA). If anyone reading this knows of a standard GA package that supports a non-metric “duality” operator please let me know (projgeom@gmail.com).

My work on “generative sculpture” grew out of my experimenting with 3D printing at the 3D Lab of the TU Berlin beginning about 10 years ago. I was interested in printing polyhedra with different sorts of symmetry. I set myself the challenge of seeing whether I could maintain the identity of the polyhedron while smoothing out the “sharp corners” at the vertices, and the “ribbon edges” paper was the outcome. (For details see my web page at the TUB). Although there was no direct connection to projective geometry in this work, I do think projective geometry can have a similar effect — compared to Euclidean geometry (or any metric geometry) it is a much more flexible and mobile geometry and contains within it many possibilities for metamorphosis and polarities characteristic of change and interaction. These I think may have to do with how form, especially living form, emerges in the first place, before it arrives at its fixed Euclidean form. There’s much work that remains to be done in this direction, I believe projective geometry itself still contains lots of surprises for inquiring minds.